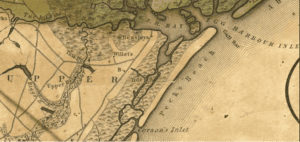

From Peck’s Beach to Ocean City

Long before the first beach tag was sold, before the smell of caramel popcorn wafted through the salt air, and before the rhythmic clack of bicycles on the boardwalk became the island’s heartbeat, Ocean City was a wild, desolate outpost. Known for centuries as Peck’s Beach, this seven-mile stretch of sand and seagrass was not a vacation destination but a rugged frontier for whalers, indigenous hunters, and even wandering cattle. To understand today’s Ocean City, we must look back to the centuries when the island was governed not by city ordinances but by the tides and the seasons.

The Namesake: The Legend of John Peck

The name “Peck’s Beach” appeared on maps long before the Lake brothers ever set foot on the sand. The namesake was John Peck, a whaler and entrepreneur in the early 1700s. During this era, New Jersey’s coastal waters were teeming with whales, and the barrier islands served as vital “staging areas” for the grueling work of the shore-based whaling industry.

Peck used the island as a base of operations. He and his crew would scan the horizon from the high dunes, and when a spout was sighted, they would launch small boats into the surf. The island served as a place to “render” blubber into oil—a valuable commodity for lamps and machinery. Although Peck didn’t build a permanent town, his presence established the island as a functional territory. For over a hundred years, the land remained essentially a seasonal work site, a place of hard labor and salty grit rather than leisure.

Native Roots: The Seasonal Sanctuary

While John Peck gave the island its colonial name, he was far from the first human to use its resources. For centuries, the Lenni Lenape people visited the barrier islands in the summer. To the indigenous tribes of the Delaware Valley, the island was a seasonal sanctuary.

They trekked from the mainland across the marshlands to harvest the bounty of the Atlantic. The Lenape didn’t build permanent structures on the shifting sands; instead, they established summer camps. They gathered clams, oysters, and fish, then dried their catch to sustain their inland villages through the harsh winter months. To the Lenape, the island was a place of abundance and a crucial link in their ecological cycle, a tradition of “summering at the shore” that predates modern tourism by half a millennium.

The First Resident: Parker Miller’s Solitary Life

For most of the 19th century, the island remained largely uninhabited during the winter. That changed around 1850 with the arrival of Parker Miller. Often cited as Ocean City’s first true year-round resident, Miller took on a role that sounds like it belongs in a lonely maritime novel.

He was an agent for marine insurance companies, stationed on the island to watch for shipwrecks and safeguard any cargo that washed ashore, a frequent occurrence along the treacherous Jersey Coast. Miller lived with his family in a modest farmhouse near what is now the intersection of 7th Street and Asbury Avenue. At the time, his only “neighbors” were the cattle and sheep that mainland farmers ferried across the bay to graze on the island’s salt hay. Imagine the solitude of a winter night in 1855, with nothing but the sound of the wind through the cedars and the distant lowing of cattle where a bustling downtown now thrives.

The Great Transformation: From Pasture to Grid

The transition from a wild pasture to a planned city began in the late 1870s. The island’s ownership had passed through many hands until the Lake brothers scouted it. They saw past the grazing cattle and the maritime wreckage, envisioning a symmetrical, orderly paradise.

In 1879, the “Peck’s Beach” identity was officially retired. The land was surveyed and divided into a rigorous grid. The surveyors laid out the streets with mathematical precision: numbered streets ran north to south, and avenues, named after states and prominent figures, ran from the ocean to the bay. This deliberate design is why Ocean City is so easy to navigate today; it was a “planned community” before the term even existed.

As the cedar trees were cleared and the dunes leveled to make room for the first 51 buildings, the wild outpost vanished. The cattle were moved off-island, the whalers were a memory, and “America’s Greatest Family Resort” was born.